2025 Data Breach Investigations Report

Today’s threat landscape is shifting. Get the latest updates on real-world breaches and help safeguard your organization from cybersecurity attacks.

Key resources

2025 DBIR

Read the complete report for an in-depth, authoritative analysis of the latest cyber threats and data breaches.

Leveraging the DBIR to stay ahead

CommScope builds advanced networks that help power our digital world. See how insights from the latest DBIR helps the company fortify those networks, which helps safeguard their customers and contributes to a more secure, interconnected society.

2025 DBIR Executive Summary

Get an overview of the most prevalent attack patterns and industry-specific vulnerabilities to help protect your organization.

Top takeaways

Explore eye-opening stats and critical findings from this year's report.

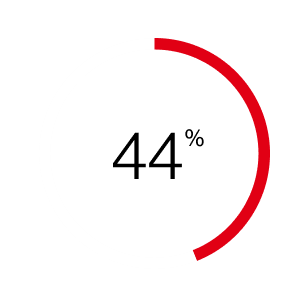

of breaches were linked to third-party involvement, twice as much as last year, and driven in part by vulnerability exploitation and business interruptions

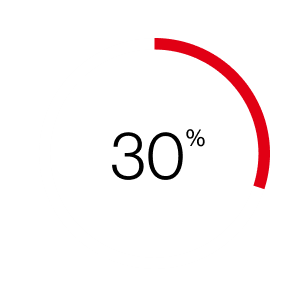

increase in attackers exploiting vulnerabilities to gain initial access and cause security breaches compared to last year's report

Snapshots

Businesses of all sizes and across all sectors can be vulnerable to threat actors. Gain actionable insights to help protect your business from potential harm.

Watch our latest webinar series

Learn from renowned cybersecurity experts as they reveal the latest threats uncovered in the 2025 DBIR, along with innovative strategies to help combat them.

On demand System Intrusion & Ransomware

Help prevent ransomware attacks, linked to 75% of system-intrusion breaches reported in this year's DBIR, with scalable, customizable security solutions.

On demand Social Engineering

Phishing and pretexting are top causes of costly data breaches. Discover how to help prevent attacks by blocking connected devices from accessing malicious sites and infected downloads.

On demand Basic Web Application Attacks

About 88% of breaches reported within this attack pattern involved the use of stolen credentials. Learn how Zero Trust security principles can minimize your attack surface.

On demand 2025 DBIR Key Findings

DBIR authors take a deep dive into the 2025 report. Gain crucial insights on emerging cybersecurity threats and attack strategies across organizations and industries.

On demand 2025 DBIR: Turning Insights Into Action

Learn from our expert panelists as they share proactive defense strategies and best practices to help mitigate risk and strengthen your organization’s security posture.

Cybersecurity Intelligence Briefings

Help prevent employee lapses and ransomware attacks that can jeopardize your organization’s finances and public image. Dive into the latest briefings and stay a step ahead.

More reports

2024 DBIR

Learn how to prepare for cybersecurity threats, no matter the size of your organization. Review real-world breaches to help evaluate potential updates to your security plan.

FAQs

The DBIR is the authoritative source of cybersecurity breach information. It’s an annual report analyzing real-world data breaches—how they happen, who’s behind them and how businesses can help stay protected. Using global data, it provides key insights that can help companies stay ahead of cyber threats.

Our data is contributed by a wide range of organizations, including international law enforcement, forensic firms, law firms, cyber insurers, cybersecurity industry sharing groups and of course, our own Verizon Threat Research Advisory Center (VTRAC) caseload. Each year, the DBIR timeline for in-scope incidents is from November 1 of one calendar year through October 31 of the next calendar year. Thus, the incidents described in the 2025 edition took place between November 1, 2023, and October 31, 2024.

Yes! The DBIR goes beyond identifying threats. With the mapping provided to popular frameworks such as the Center for Internet Security Critical Security Controls, it offers a roadmap for what you can do to help combat the attacks you may possibly face. It highlights common attacks and vulnerabilities while providing expert strategies to help mitigate risks, from access controls to employee training.

No security strategy is foolproof, but businesses can help reduce risk by:

- Using multifactor authentication (MFA) to block unauthorized access

- Keeping software updated to fix security gaps

- Training employees to spot phishing and threats

- Encrypting sensitive data for added protection

- Testing security defenses regularly

- Having an incident response plan in place